Did you know that business is all about expectations?

Imagine one day you get an invitation to a private 10-lecture master class on the fundamentals of business. You take the train North from London to Cambridge, UK and proceed to follow a long series of elaborate directions — locating academic buildings, chasing various landmarks and carefully observing your surroundings to leave no trace and blend in without being followed. The path leads you underground where after a couple of near slips on the narrow stairs you proceed to knock on an expired wooden door. Inside you most uneasily find yourself in the company of the strongest entrepreneurs, world leaders, cyber revolutionaries and other influential individuals.

They don't notice you, their attention is fixed instead on an animated suited gentleman in front of the class who is decorating the blackboard. The first class has begun and the professor, an ex-theoretical physicist turned hedge fund billionaire is completing the sketch for this class.

“Expectations is where business starts and ends,” he says, temporarily distracting your attention from the equations on the blackboard. He did not use the word 'profit'. Nor did he say 'value', not even 'shareholder returns' or 'customer satisfaction' or anything else that came to your mind. He said 'expectations'.

You glance again at the black board, trying to understand what you are missing.

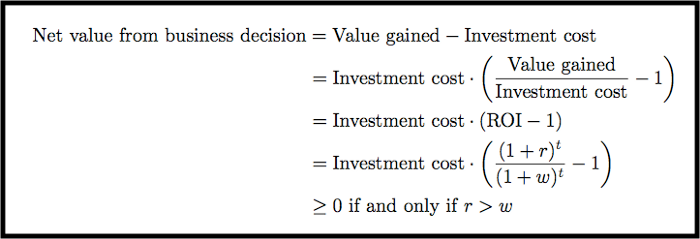

He has shown that the value from a business decision is proportional to investment size and excess return on investment. Following that, assuming your company can earn an annual return of r, collected at time t, the decision is favorable to the business as long as the return exceeds investor expectations (also called cost of capital)— w. So underpinning all of business is the simple formula r > w or beating expectations.

Side note

It is important to note that these are not expectations placed on your business, but expectations placed on the class of businesses like yours. An investor might expect an 10% annual return on your class of company, but expect a 15% return from your company based on analysis of your past years' financials . Beating 15% is good, beating 10% is critical for your company to still represent a valuable investment for the investor.

Examples

In venture capital, this means no investment decision will be made unless the company could offer a significant return, matching investor expectations about this high-risk asset class.

In a lemonade stand situation, let's assume your mother is the principal investor. She could have certain expectations on your profit levels “It's the summer season. I would like to earn back this investment in two weeks or you will have to shut down”.

It is a delicate matter to apply this principle to employees (it is more appropriately applied to departments), but often performance is linked to expectations in role. Exceeding them results in a bonus and not meeting them consistently may result in redundancy.

Implications

To some this is a trivial exercise, but there are many implications that don't necessarily sound obvious:

- The longer your benefits take to accrue, the higher the overall return needs to be. Annual return is much more important than overall return

- Decisions that “make money for the business” but don't help exceed investor expectations should not be taken lightly. This is simply why a start-up company could never get away with taking investor money and investing it in government bonds (unless of course it was an asset management start-up)

- To stay funded, you need to beat returns of companies in the same class (technology companies, e-commerce companies, beer producers, hotel chains, etc.). There will always be investors attracted to your class of asset due to their expertise, views of the future or risk profile of remaining portfolio

The more you think about it, the more it makes sense. So what is next…

As you wonder that, you have woken up. You are back at home surrounded by a half-closed laptop, random papers and a nearly-empty glass of orange juice. It is the middle of the night and the room is half-lit from the lights of the city. You now know you want to be an entrepreneur. You know that you have to become one, so that maybe one day — if you get to dream again —you could attend that second class.